They say, ‘ Behind every great man there’s a great woman’. Few people know that this was originally a slogan of the feminist movement in the 1940s. And I think even fewer people think about its true meaning. In fact, it’s about real women who got stuck in the shadow of their husbands because, in most cases, they simply just had no other choice. For social, cultural, or economic reasons, they had no opportunity to express themselves or to work independently. The latest part of my Women’s montage series is also about a woman in the shadow. Despite the fact that Mileva Maric was a distinguished scientist and could be credited with many achievements, she is almost unknown. When she’s mentioned, she’s at most referred to as Albert Einstein’s first wife (and not necessarily in the most favourable light). For example, if you Google her, the following results come up.

“Einstein’s forgotten wife”, “The hidden woman behind Einstein’s success”, “In Einstein’s shadow”.

It also didn’t help that Einstein spoke mostly negatively or not at all about his ex-wife. But let’s not get ahead so quickly. Suffice it to say that while researching Mileva Marić’s life, I realized a few things. First of all, there are very few articles about her life, and most of them are also rather superficial and simplistic. Most articles focus mainly on her role as Einstein’s wife, and nothing more. But Mileva was much more than that. And in this blog post, I will try to give you as much detail about her life as possible.

- Early years in Serbia

- Unless she is acted upon by a force in Zürich.

- Opposites attract!

- What’s in a name? Mileva Marić?

- Planning is a human thing.

- Bern, Hans-Albert, and the happy scientist couple

- One gets the pearl, the other the box.

Early years in Serbia

Mileva Marić was born in 1875 into a wealthy landowning family in Titel, present-day Serbia. Interestingly, her family is still often mistakenly referred to as Hungarian (even in the Einstein House in Bern), because her hometown was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time. Despite this, we know from a number of surviving correspondences that Mileva and his family identified themselves as Serbian.

Unlike other kids, she showed a great interest in books and learning, especially in science, from a very young age. The main reason for this was a congenital hip defect, which caused her left leg to be shorter, so she walked with a slight limp. She could not play with her siblings or other children and her classmates often mocked her, which is probably why she fled into the world of books. Her father noticed her special interest early on and supported her in all her ambitions.

The first steps

This didn’t just mean that he gave her books or sat down with her to study. It was much more than that: he helped Mileva to get a proper education (as a girl!!!), which was quite unusual at the time. So, from the age of 11, she attended secondary school. Then, she went to a boys’ grammar school with special permission, where they allowed her to take physics lessons. It may not seem like a big deal nowadays, but back then it was a huge achievement. Don’t forget that the first girls’ high school in Serbia didn’t open until 1905, and not everyone could get in.

Since Switzerland was already allowing women to study at a higher education level, Mileva moved to Zurich at the age of 19. So first, she graduated from high school, and later she began her university studies. We know of this period that Marić worked hard to catch up with his male classmates, but she did not spend her free time exclusively studying. She was an excellent singer and pianist and was also interested in literature, astronomy, and languages. Speaking of languages, practically all the publications forget to mention the fact that besides her mother tongue, Mileva also spoke fluent German and Hungarian.

Unless she is acted upon by a force in Zürich.

Marić enrolled at the University of Zurich in 1896, majoring in mathematics and physics, with the aim of obtaining a secondary school teaching qualification. She was the only woman to gain admission in her group and the fifth woman in the history of the university. You can imagine the joy, pride, and determination with which she pursued her goal of becoming a scientist. During her university years, she stayed at the Pension Engelbrecht, a boarding house for women. It was home to foreign students, mostly from countries where women’s higher education was not allowed or was limited.

It was here that she met the most influential friends of her life, Helene Kaufler-Savić and Milana Bota, with whom she remained close friends for more than 30 years. The boarding house was also a real community, with the girls often getting together. On weekends they would go on long hikes in the surrounding woods and in the evenings they would play music together. On such occasions, Einstein would often appear and accompany them on the violin. The novel Frau Einstein gives a good insight into what these get-togethers might have been like.

Speaking of Einstein, it was around this time that Mileva met a young, 18-year-old Albert Einstein. Their relationship was certainly platonic at first, they considered each other as university classmates, then friends, and over time grew into love. One would think that there could not be a more beautiful relationship that blossomed into love. And indeed. Their correspondence suggests that they made each other happy in every way during the first years of their relationship. They connected not only emotionally but also mentally, which seems essential for two such intelligent and talented people. Einstein himself said of their relationship that he was happy to have found a creature who is his equal, and who is as strong and independent as he is.

Opposites attract!

Although they were quite different from each other, Marić had a good influence on Einstein. Mileva was a reserved, determined, serious girl, while Albert was fun, bohemian, and spontaneous. Einstein repeatedly mentions in his letters that Mileva makes it easier for him to learn, and his systematic approach is a great help to him.

In 1900, the final exams arrived, and Mileva surprisingly failed them. Her grades in her written exams were perfect, she finished the year with a 4.7 average (better than Einstein’s, by the way), but she did not do well in her oral exams. I could not find a clear explanation for this big difference. Some suggest that because of her personality she could express herself better in writing. Others suggest that she experienced discrimination because of her gender. Nevertheless, Marić did not lose hope. She was not the first person to fail the final exam on the first attempt. She decided to try again the following year.

What’s in a name? Mileva Marić?

Mileva spent the summer of 1900 at home in Serbia. She returned to Zurich in the autumn semester and began her studies with fresh enthusiasm. This time she moved not to the Pension Engelsbrecht but to a small apartment where Einstein was a very, very frequent guest. In her letters to Helene, she described this period as a very happy one. She wrote a lot about Albert, how happy they were together, and also about their scientific work together.

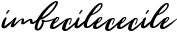

They finished their first joint research in December of that year. It was published in 1901 under Albert’s name in Annalen der Physik (one of Europe’s leading physics journals at the time). Fontos, hogy ez volt az első tudományos cikk, melyet Einstein neve alatt publikáltak. Notably, this was the first scientific paper published under Einstein’s name. But there’s a valid question:

Where is Mileva Marić’s name?

Well, there were several reasons why they decided not to mention her. At that time women were not taken seriously enough to add their names to scientific papers. One could say that the value of the work would have been ‘diminished’ if Mileva’s name had appeared. Another reason was that Albert had to get a job so they could get married. And a paper in a scientific journal was the perfect way to prove his scientific work and his ability. So Mileva was therefore happy to make a small sacrifice. Why Einstein did not give Mileva credit for her contribution later is another matter.

Despite all this, Einstein was still unable to find a job and he needed to move to Milan to live with his parents. This was a difficult decision not only because it kept the lovers apart, but also because of the Einstein family’s relationship with Mileva. In particular, Einstein’s mother considered their relationship undesirable because she thought the girl was too old (three years elder) and too intellectual. And on top of that Mileva was not even Jewish, she was Slavic. However, as there was no proposal, Albert and his family stopped fighting for a while.

Planning is a human thing.

Then, in the spring of 1901, the lovers took a “fateful” trip to Lake Como, which changed the young physicist’s life forever (Mileva’s, not Albert’s). The girl became pregnant. Although this was not as socially despised as, say, a few decades earlier, pregnant unmarried women were still disapproved of. A girl was thought to be a disgrace not only to herself but also to her family. So the couple had to think of something. Albert would find a job as soon as possible, and Mileva would pass her final exams. They would get married secretly and then present their parents with a fait accompli. Unfortunately, none of them happened. Einstein was unable to find work because of rising anti-Semitism and his peculiar sarcastic style. And Mileva failed the exam a second time.

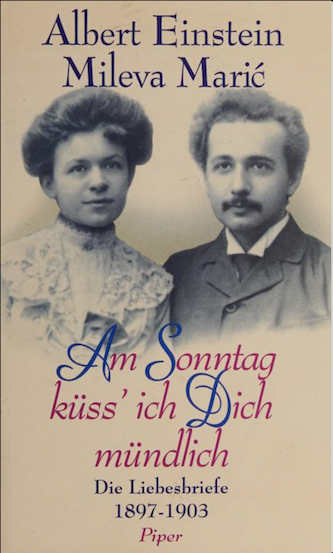

After that, she had no choice but to travel home to her parents’ house to give birth to her first baby. We know very little about the fate of the child. What we do know for sure is that she was born in Serbia sometime in 1902, but the exact birthday is unknown. Nor do we know her real name, Mileva and Albert refer to her as Lieserl in their letters. We know almost nothing about the rest of the child’s life as if she had never existed. It is assumed that she was either adopted or died of scarlet fever at a very young age. Einstein probably never even met her. From 1903 onwards, there is no mention of her in any form, not even in their correspondence. What is certain, however, is that the loss of Lieserl had a lasting effect on the relationship between Mileva and Albert.

Bern, Hans-Albert, and the happy scientist couple

Mileva and Albert finally married in 1903, after Einstein’s dying father finally gave his blessing. Albert got a job in Bern, so the couple settled in the Swiss capital. This turn of events not only marked the beginning of Einstein’s triumphal success, but also the beginning of the downturn of Mileva’s independent scientific activities. It was at this time that she became more and more preoccupied with daily housework. However, we cannot yet say that Marić has completely turned away from mathematics or physics. During this period, for example, she was still attending meetings of the Akademie Olympia Club, a scientific society founded by Einstein and his friends. In 1903 she also contributed to the construction of a machine for measuring small electrical currents.

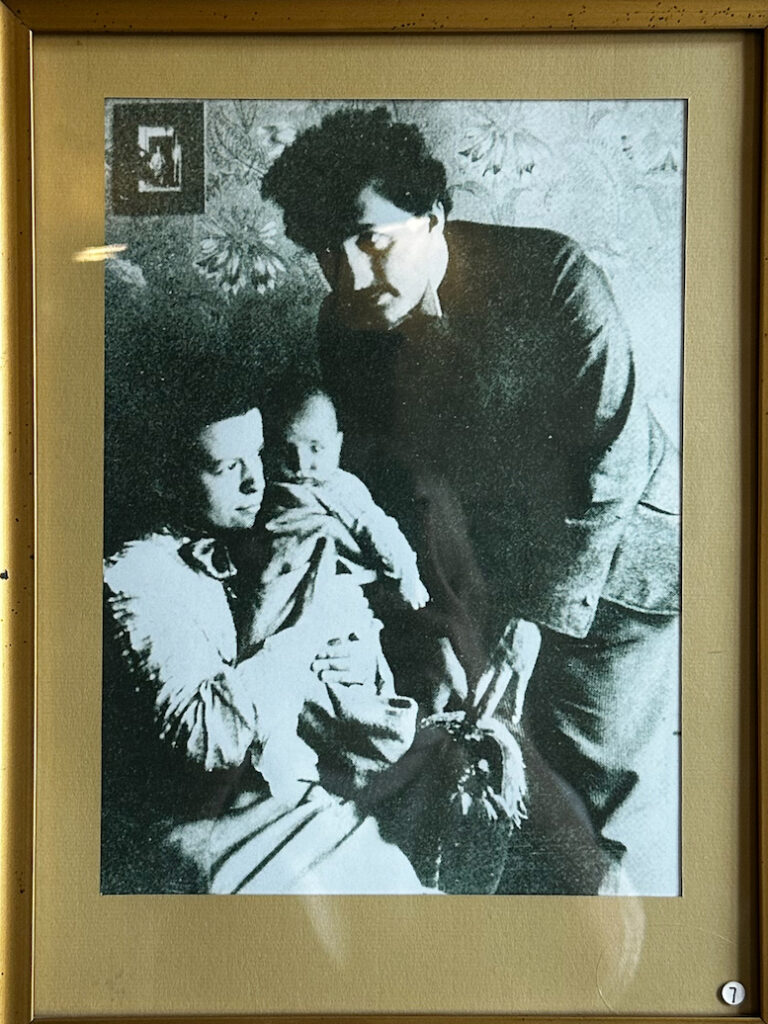

They often invited guests who described them as a dream couple. On such occasions, they had big dinners, played music, and engaged in scientific discussions. From various correspondence, we learn that their friends thought the calm Mileva was a great match for the unpredictable Albert. In 1904 she gave birth to their first son, Hans-Albert. They were extremely happy. Although Mileva’s energy was running low as she continued to take an active part in her husband’s scientific work, in addition to housework and raising their son.

One gets the pearl, the other the box.

After the baby was born, Mileva’s brother Milos visited the Einstein family. In his letters, he recalled how the couple had worked late hours on various research projects. Based on his letters and similar testimonials, we believe that Mileva was more than just a wife, and in fact, was actively involved in Einstein’s success. But Marić never received any recognition for her work from the scientific community of her time. This may have been due to Mileva’s somewhat introverted nature and Einstein’s highly extroverted and often selfish attitude. However, posterity has made many attempts to rehabilitate Mileva Marić’s reputation as a theoretical physicist.

The hard work soon paid off. In 1905, Albert Einstein published five papers (only under his own name, of course), one of which formed the basis of the theory of relativity, and another which later won him the Nobel Prize. From Einstein’s correspondence, we know that in the following years almost all his thoughts were occupied with his work and that he had little time for his wife and children. Thus, despite the joys of raising children, Mileva felt lonely and that Albert considered his scientific work more important than his family. At this point, it is interesting to think about how the following years would have turned out if they had been able to stay on the same intellectual level.

Not long ago we finished a very significant scientific work that will make my husband world famous.

Mileva Marić

In the following part of the Mileva Marić series…

I will focus on the second half of Mileva Marić’s life. I will tell you about how Marić lived while her husband was on his way to world fame. And I will describe the consequences of the First and Second World Wars on the family’s life. So if you don’t want to miss the next post, follow me on Instagram.

Sources, references:

In Albert’s Shadow: The Life and Letters of Mileva Maric, Einstein’s First Wife by Milan Popovic and Mileva Einstein-Maric

Mileva Maric: Life with Albert Einstein by Radmila Milentijević

Frau Einstein by Marie Benedict

https://www.uni-heidelberg.de/de/universitaet/heidelberger-profile/historische-portraets/mileva-maric-die-fast-vergessene-einstein

https://www.thefreelibrary.com/The+professional+emancipation+of+women+in+19th-century+Serbia.-a0357472010

https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/the-forgotten-life-of-einsteins-first-wife/

https://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/mileva-einstein-vom-scheitern-in-der-physik-und-in-der-liebe-100.html

https://womenyoushouldknow.net/mileva-maric-einstein/

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mileva_Mari%C4%87

https://archive.org/details/amsonntagkussich0000unse/page/96/mode/2up

phrases.org.uk/meanings/behind-every-great-man-theres-a-great-woman.html